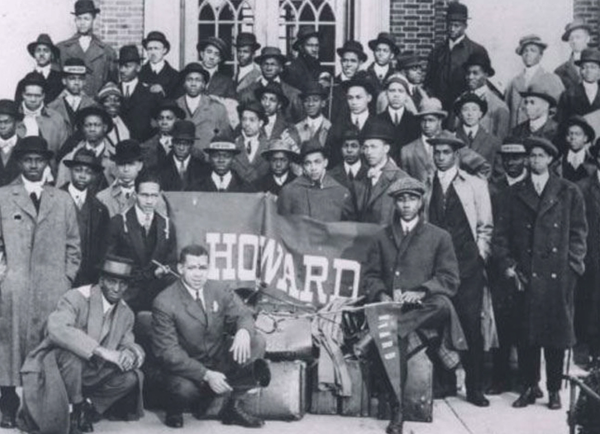

Celebrating Historically Black Colleges and Universities

📚 The history

While a few Black universities were founded prior to the Civil War, the years following the abolishment of slavery saw an HBCU boom in which many of today’s institutions were founded, primarily located in the South, including Morehouse College and Alabama State in 1867.

- However, many of these schools had white founders with deeply problematic beliefs about the intelligence and capabilities of Black individuals. Despite this, Black students who could not attend other Southern institutions due to segregation continued to enroll.

Today, there are over 100 HBCUs that educate about 10% of all Black American college students while accounting for only 3% of the nation’s colleges and universities. And in a climate where U.S. undergraduate enrollment is down nearly 10%, HBCU applications rose almost 30% from 2018 to 2021.

- HBCUs today are primarily run and operated by members of the Black community and have recently seen an increase in financing and attention. The Biden-Harris administration (vice president Kamala Harris is the first HBCU grad in the White House!) has also focused on increasing HBCU funding and resources.

- Making education affordable, accessible, and safe for young Black students has allowed HBCU athletes to write richer history on and off the field.

🏈 The sports

SOURCE: BLACK COLLEGE FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME

While most Northern schools were technically desegregated by the early 1900s, many Black students — and student-athletes — still preferred HBCUs and the safety from racial harassment they provided.

- In the late 1800s, students at Black colleges began organizing sports teams in response to segregation in collegiate athletics. By 1912, the Central Intercollegiate Athletic Association (CIAA) was formed to regulate competitions between the schools.

HBCUs primarily competed in football, basketball, and baseball and, while many southern, predominantly white institutions (PWIs) refused to play Black teams out of fear of losing to them, HBCU squads were known for excellence — particularly on the gridiron.

- For example, the Florida A&M Rattlers had a 204-36-4 (!!!) record between 1945 and 1969.

- Due to an unofficial ban on Black players in the NFL that lasted until 1946, it wasn’t until Grambling State fullback and linebacker Tank Younger broke into the league with the LA Rams in 1949 that an HBCU player stepped on the pro field.

Some college athletic departments refused to integrate until well into the 1970s — the SEC didn’t even begin the process until 1967. For many, it was the desire to win, rather than ethics, that finally spurred change.

- PWIs began to heavily recruit Black athletes and these wealthier white schools (with better facilities and more media coverage) soon created a recruiting gap that still exists today.

- Black students accounted for a small percentage of the population at NCAA DI schools, but in 2022, Black athletes comprised 48% of D1 football players, 55% of men’s basketball players, and 44% of women’s basketball players.

Despite the financial barriers and recruiting challenges, HBCUs continue to grab national (and international!) attention: North Carolina A&T sent four track & field athletes to the 2020 Tokyo Olympics and two — Trevor Stewart and Randolph Ross Jr. — won medals for Team USA (two golds and a bronze).

💪🏾 Notable alums

SOURCE: NINERS WIRE - USA TODAY

Long before Title IX was passed in 1972, HBCUs were championing female athletes, who, unsurprisingly, left indelible marks on the sporting world.

- After graduating from Florida A&M in 1953, Althea Gibson helped break the tennis color barrier, and, in 1956, became the first Black athlete, male or female, to win a Grand Slam. She ultimately won 56 career titles, 11 of them at Grand Slams. The original GOAT.

- On the track, Tennessee State sprinter Wilma Rudolph raced to three gold medals at the 1960 Olympics, making her the first U.S. woman to nab three golds in a single Games.

- Cheyney’s Yolanda Laney led her basketball team to the first-ever NCAA championship game in 1982, and the Wolves are still the only HBCU to contend for a title. Because the WNBA didn’t yet exist, the All-American guard played pro in Europe, but her daughter, Betnijah Laney, currently hoops for the W’s NY Liberty. Path? Paved.

Some of the NFL’s biggest names came out of HBCU programs, including renaissance man Michael Strahan as well as wide receiver Bob Hayes, who competed in both football and track during his time at FAMU before winning gold in the 100m sprint at the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, the same year he was drafted by the Dallas Cowboys. No biggie.

- Mississippi Valley State alum Jerry Rice is well-known for his success as a wide receiver with the San Francisco 49ers, leading the squad to three Super Bowl championships in the late ’80s and ’90s.

- Grambling State alum Doug Williams made history in 1988 with the NFL’s Washington Commanders when he became the first Black quarterback to win the Super Bowl and be named Super Bowl MVP.

- The Chicago Bears’ Walter Payton spent his college years at Jackson State before breaking records as an NFL running back in the ’70s and ’80s. And Alcorn State alum Steve McNair set an FCS record in passing yards before playing for the Tennessee Titans in Super Bowl XXXIV.

✨ The culture

SOURCE: JOHN KORDUNER/ICON SPORTSWIRE VIA GETTY IMAGES

HBCU marching bands are second to none. While early U.S. collegiate bands were military-inspired, HBCU bands began to add choreographed dances with upbeat moves in the 1940s and have only raised the stakes since.

- The best of the best compete at the annual National Battle of the Bands.

Most U.S. schools have a homecoming weekend, but HBCUs have an entire week. Even Queen Bey paid homage to HBCU homecoming culture in her 2019 documentary and her epic Beychella performance.

- Usually culminating with a major rivalry football game, alumni return to campus for social and philanthropic events throughout homecoming week.

Like many U.S. universities, Greek life is also an integral part of HBCU campus life. But the “Divine Nine” (Black Greek Letter Organizations) have their own distinct style, most notably on display during step and stroll shows.

- The choreographed routines put TikTokers to shame and often include signals, calls, whistles, and moves that are unique to each organization. The hype is real.

➡️ The present and the future

SOURCE: CHASE STEVENS / AP

HBCUs have molded some of the most prominent Black thinkers and leaders in U.S. history, like the aforementioned Harris as well as Martin Luther King Jr., Oprah Winfrey, Thurgood Marshall and Stacey Abrams. And what’s even more impressive is that these schools did so with a fraction of the funding many PWIs benefit from.

- For example, from 2003 to 2015, funding of private HBCUs decreased 42%, a blow to the already historically underfunded institutions.

In response to this, the Biden administration delivered over $5B to HBCUs during the COVID-19 pandemic, and private philanthropists have also stepped up to the tune of billions of dollars. There’s still a long way to go to achieve equity, but it’s a start.

- HBCU institutions, students, and the brands that love them are also demanding more. Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee, just launched the first HBCU women’s gymnastics program last year, and Talladega College in Alabama followed suit, adding a team for this season.

All of these moves are investments in the future of HBCUs and the students they serve. These institutions are massively important in providing safe spaces for students to learn and play, while continuing to grow their rich culture and traditions. We’ll step to that.

Enjoying this article? Want more?

Sign up for The GIST and receive the latest sports news straight to your inbox three times a week.